Blog

A Vibrant Renaissance in Lesbian Fashion: Redefining Style Beyond Stereotypes

Women are challenging conventional fashion norms by blending silky garments with butch suiting, making bold statements both on the red carpet and in everyday life.

Earlier this year, actress Kristen Stewart graced the cover of Rolling Stone in a black leather vest adorned with pockets, reminiscent of attire from 1980s lesbian bars. Bare-chested with a distinctive mullet haircut, Stewart wore only one other piece of clothing: a white jockstrap, into which her hand provocatively delved past the wrist. The 34-year-old, who first gained fame in 2008 as the teenage lead in the “Twilight” movie series and publicly came out in 2017, appeared to be embracing a sense of personal pleasure and autonomy.

In promoting “Love Lies Bleeding,” her queer thriller produced by A24 and released in March, Stewart continued to embody this bold, unapologetic spirit. At the Sundance Film Festival, she sported a sea green Dickies bomber jacket over a midriff-baring crop top. On “Late Night With Seth Meyers,” she appeared in a structured black leather blazer paired with a fishnet bra, further pushing the boundaries of conventional fashion and asserting her identity.

The press-junket wardrobe showcased a newly joyful and exuberant aesthetic emerging among a generation of lesbians and young queer stars. This approach to fashion emphasizes mixing overtly sex-forward, often hyper-feminine pieces with tailored, traditionally butch wardrobe staples. “It’s so playful and obnoxiously sexy,” says New York-based fashion designer Daniella Kallmeyer, 37. “It’s not about a ‘typical’ look. There’s no stereotypical way to dress queer or like a lesbian. It’s about unapologetically owning your identity.”

In January, singer Reneé Rapp wore a hot pink bustier paired with a silky blazer to the premiere of the “Mean Girls” remake, while singer Billie Eilish attended the Golden Globes in a bulbous black Willy Chavarria suit jacket. The March issue of Vogue featured actress Ayo Edebiri donning barely-there miniskirts with wildly oversized button-downs, further reflecting this vibrant, boundary-pushing fashion movement.

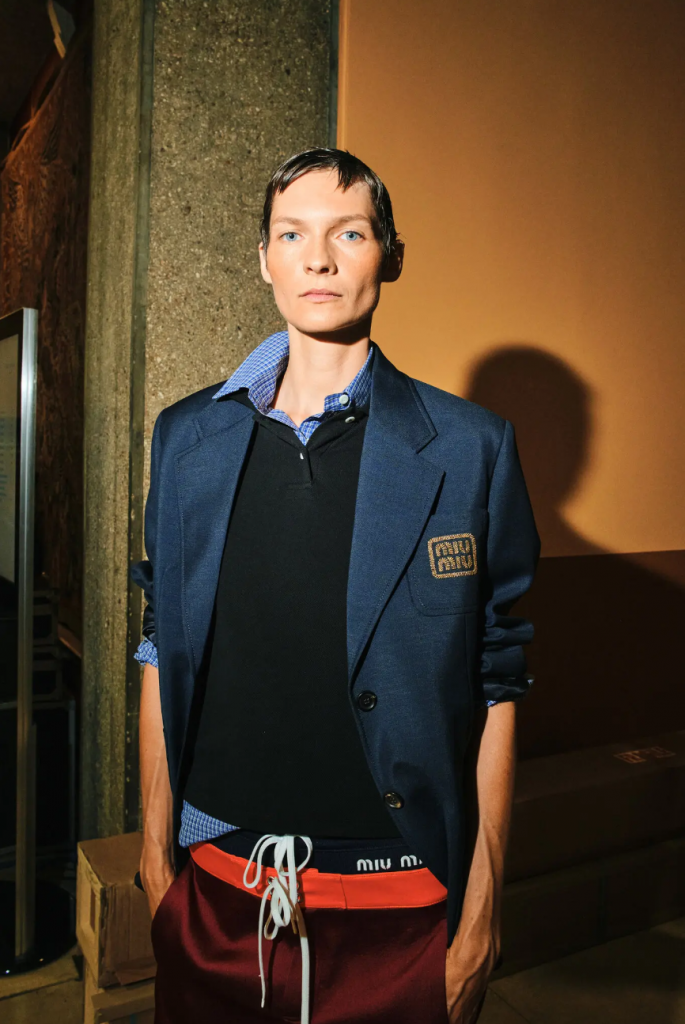

Even celebrities who don’t identify as queer are embracing this gleeful, nonconformist approach to fashion. Rihanna, for instance, sports a cropped haircut and black necktie in the April issue of Interview, while Anne Hathaway graces the cover of V Magazine’s summer issue in a velvet, linebacker-shouldered three-piece suit under the headline “His and Hers.” This defiant attitude also made its mark on the spring 2024 runways. At Maison Margiela, models strutted in disheveled oversized suits with frizzy hair, and at Miu Miu, Miuccia Prada presented a collection of rumpled polos and boat shoes, evoking the image of models raiding a British boy’s school.

While the disruption of gendered fashion norms in the mainstream may seem novel, this style has historical precedents. In 1653, French artist Sébastien Bourdon painted Swedish monarch Christina in a languid black silk dress layered over a white linen shirt, tied at the collar in a style typically worn by men. Christina, who had already refused to marry, abdicated the throne the following year and took on numerous lovers of both genders in Rome. Nearly two centuries later, American artist Romaine Brooks painted a generation of Parisian lesbians in “new woman” bobs, monocles, and tailored jackets. After World War II, the clash of masculine and feminine aesthetics intensified due to the enforcement of laws like New York’s 1845 “three-piece clothing law,” which required women to wear three articles of “feminine” clothing (bra, underwear, and skirt) or risk arrest during frequent raids on queer bars. In these dimly lit spaces, butches sported tailored suit tops and narrow navy skirts, using fashion as a crucial signifier to forge community and perhaps find love.

It’s not surprising, then, that as the rights of women and queer people face renewed threats, lesbians are asserting their autonomy through fashion. “In the past decade, the political landscape encouraged queer visibility in various forms, but now politicians are attempting to squash that visibility,” says writer Eleanor Medhurst, whose book, “Unsuitable: A History of Lesbian Fashion,” will be released this month. “Queer women are pushing back against that with fashion, which can play a really important role in making ourselves visible in the world.” For women of any sexuality seeking to affirm their agency through clothing, lesbians provide a powerful example, having long been excluded from traditional femininity’s pillars of marriage and motherhood. Lesbian fashion has always transcended mere clothing; it embodies a vision of a truly liberated world that does not yet exist.

Skip to content

Skip to content